Photo © Kevin Thom

The improv blog with attitude.

Photo © Kevin Thom

“Everything I’ve ever gotten has come to me when I stopped trying to get things, and focused on finding and performing in my own voice. So, make sure the bulk of your time is spent on projects that are truly unique to you and keep you up at night with excitement, not projects that showcase your castability.

I’d also say don’t get married to one path. I see a lot of people who let the fact that Second City or SNL has not hired them cause them to become bitter and/or quit comedy. I think it’s healthier to set goals like, ‘I want to be working with friends and producing interesting comedy for a living sometime soon,’ than ‘I need to get Second City Mainstage by 2012 and SNL by 2015 or I’ve failed.’

Lastly, don’t spend any energy worrying about what other comedians have been hired for, whether they deserve it, whether their last joke was good or not… Just worry about your own stuff and do your best to enjoy all the hilarious people out there without judgement. All easier said than done.”

Source: Live From New York It’s Saturday Night Live blogspot

Improvisers tend to be oddballs, artists, and nerds. So it’s not surprising most teams tend to dress like college students – or worse.

Even if you do improv strictly for fun, you’re putting on a show for an audience. How you present yourselves is an opportunity to stand out from the dozens (maybe hundreds?) of other teams in the city. Some of the longest-running and best-loved ensembles have a look that’s instantly identifiable…so why not yours?

Jeans and t-shirts are fine, but crazy patterns, big logos, and funny slogans can distract from your character and even “vampire” the whole scene. If you stick to solid colours, you’ll create a unified look without looking stuffy.

And take it from one who learned the hard way: do the “bend over” test in your jeans beforehand. You don’t want your ass crack to be what people remember about your set. (Same goes for the cleav, ladies.)

Some teams kick it up a notch, which – if you can manage it on an improviser’s budget – is a nice touch.

Todd Stashwick’s team, Burn Manhattan, wore Reservoir Dogs-style suits and skinny ties back in the day. And Toronto’s Surprise Romance Elixir dons wedding attire (suits for the guys, dresses for the girls) in keeping with their wedding-themed show.

The best teams manage to look cohesive and comfortable. Their clothes are simple and non-descript enough that they don’t detract from whatever the scene is about.

Here are some of our faves:

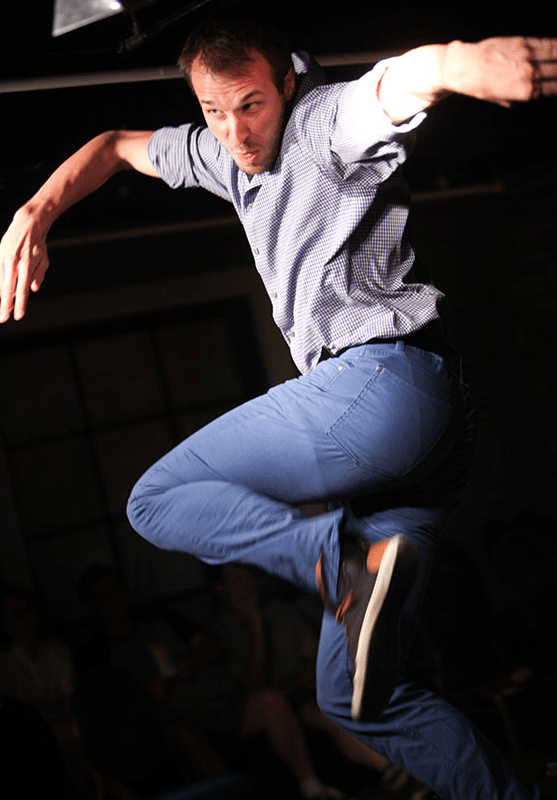

TJ and Dave’s standard attire of plain shirts, khakis or dress pants, and sneakers or suede shoes, allows them to play a plethora of characters, from the mundane to the ridiculous.

Mantown’s v-necks or checked shirts, jeans, and omnipresent beers are a staple sight for fans of the improvised frat party.

Chicago’s Improvised Shakespeare favours Elizabethan clothing (on stage, anyway).

Pop, Don’t Float

Whatever you choose to wear, remember that people want to see you. You can be doing something crazy physical, but if your clothes don’t “pop” against the background, most of what you’re doing will be lost.

If the curtain or backdrop is black, brown, burgundy, or some other dark or dominant hue, avoid wearing those colours, or you’ll suffer from what Larry Sanders called the “floating head” syndrome. (Think of Zach Braff in Garden State.)

Lastly, you don’t all have to dress the same, but common colours, garments, or other elements will help unify the team visually.

Bottom line? Look like you’re worth paying to see perform.

Cook County Social Club rocks nerd chic for the camera.

Photo © Kevin Thom

If you’re a comedian living in Canada, it’s likely you’ve heard about this Guy Earle case. And for good reason.

In 2007, while dealing with a table of hecklers (Lorna Pardy and her girlfriend), stand-up comedian Guy Earle let loose a series of lesbian jokes (maybe homophobic slurs?) which later brought him in front of the Human Rights Tribunal. He lost the case and was forced to pay $15,000, which coincidentally is the annual income of the average stand-up comedian.

Last week the Supreme Court of British Columbia upheld the ruling.

So what does that mean for you, an improviser working (for free, probably) in Canada?

You have to deal with the audience’s suggestions every night. And most of those suggestions are “dildo.” What rights do you have?

Plus, you’re not perfect. Some scenes work, others fail. Most new jokes fail. And like all comedians, you love pushing boundaries. (Have you ever seen the Catch-23 improv game, “More Rape, More Retarded”? You’re probably better off if you haven’t…)

The question for every comedian in Canada is: What jokes are in your act that could get you pulled in front of the next Human Rights Tribunal?

More importantly, is Canada still a safe place for edgy, alternative comedy?

This question bothered me so much, I spent a weekend with a bottle of Glen Livet and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and found out the answer. And it’s yes. Surprisingly, yes. Canada is a great, safe, liberal place to make jokes at the expense of others. But there are some limitations.

With the help of a few lawyer friends, I put together some easy guidelines (not actual legal advice, they made me say that), to prevent you from accidentally joking your way into Guy Earle-like martyrdom.

The Guy Earle case has taught me how much freedom we as comedians actually have, and how one stand-up could get absolutely everything wrong in a single set. So let’s get started…

1. There’s a big difference between playing a paid set and an open mic.

At an open mic or an improv jam, you’re a patron of the club just like everyone else. But as soon as you become a paid comedian, you could be considered an employee of the club. Now you’re subject to workplace discrimination laws, which are more restrictive than the “freedom of expression” afforded to you in the Charter.

Guy Earle wasn’t charged for Hate Speech (inciting violence towards a minority group, one of the few limitations of free speech), but rather discrimination in the workplace. Section 8 of the Human Rights Code protects minority groups from being harassed while obtaining a service available to the public. The Supreme Court ruled the heckler (Ms. Pardy) had the right to hear Earle’s act without being singled out as a “stupid dyke.” [324]

2. Your jokes about ethnicity, sexuality, and gender are protected by the Charter of Rights and Freedom.

Even if you’re being paid, most jokes you make are protected as free speech. Even if they are offensive. Even if they aren’t funny. Even if they seem racist, sexist, or homophobic to your audience. Or if you clumsily parade sensitive topics like rape, incest, or the Holocaust. You are welcome to act like a bigot onstage, provided you can argue that these jokes “expose prejudices” of bigots. [336]

Guy Earle argued that his interaction with Lorna Pardy was satirical: “an aspect of self-realization for both speakers and listeners.” Which is kind of insane. He argued he was pointing out the problems with homophobia, by directing slurs at an actual lesbian. But if the same exchange had occurred between two comedians onstage (or at least not directed at a specific audience member), Earle’s case may have been summarily dismissed. [453]

3. Leave what happened onstage, onstage.

When hosting a comedy event, you have to shut down hecklers. It’s one of your few jobs. (Others include pretending that last act was funny, continually asking: “Is everyone having a good time?” and sitting in the green room playing Kingdom Rush on your iPad.)

But shutting down a drunk, belligerent heckler is when things can get out of hand.

Do what you need to onstage, but don’t continue the conflict at the bar. Go home. Have a smoke. Get back together with your ex. Do whatever it takes to stop yourself from re-engaging with your heckler.

A big problem for Earle was that he continued to call Pardy names after the set was over. He even escalated events by breaking her sunglasses. It was impossible to justify Earle’s comments as “performance” after it continued away from the stage. [330]

4. A “justified response” has a lot to do with what has come before, and what your peers are doing.

Shutting down a heckler is a common practice in comedy. How other comedians deal with the audience is a great benchmark for how you should treat your audience. If you can prove your jokes are common practice, then it’s harder to suggest discrimination.

You don’t have to perform the same jokes, sketches, or shortform games as others, but as long as you’re in the same ballpark, these could be argued as “common practices.” But as my lawyer friend explained: “ultimately, it depends on context.”

One of Earle’s biggest problems was that he couldn’t prove his conduct was typical for a comedy club. Not when he personally dealt with hecklers. And it wasn’t part of his act. He couldn’t even prove that it was an average response for other stand-ups dealing with a hostile crowd. This part of the ruling made me wonder if Earle was even trying to win the case. [332]

5. Clearly establish the heckler before ripping into them.

Asking “Who just said that?” is great protection for comedians. Shutting down a heckler is common practice (so it has a justified response), but accosting a random audience member out of the blue is not. Just make sure you have the right person first, then let your Reign of Burns begin.

Improvisers might also think about getting consent before bringing an audience member onstage. Or riffing with them in the crowd. You might be able to argue that by agreeing they are now a participant in the show. Which is an entirely different legal relationship.

Earle’s lawyers argue that just by Ms Pardy calling out, she involved herself in the show, making anything said part of the show. Unfortunately, no one could prove Ms Pardy heckled during the show. None of the other comedians or witnesses could confirm that fact. Another major fail for Earle. [323]

6. This isn’t legal advice at all. It’s common sense: don’t be an asshole.

It has happened to every comedian I know. Something goes wrong in your set. You offend someone and then during or after your set you are confronted. Maybe you break every guideline listed above. If you do, find that audience memeber and make it right with them.

That doesn’t mean you have to apologize for your joke. But sympathize with their concerns. Try to explain your perspective on why what you said onstage is important. Don’t expect to change their viewpoint, but just by listening you lessen their outrage. The less angry they are, the less likely they are to take legal action.

Lorna Pardy has spent the last five years dealing with lawyers, testifying in court, and dealing with appeals. That’s a massive commitment of her life. No one wants to take legal action. No one thinks “I’ll sue that comedian wearing Modrobes pants from 1995 and then I’ll be rich!” They do it because their beliefs are important to them, and if they don’t stand up to you, no one will. So make it easier for them. Let them be heard.

Personally, I think Guy Earle could have prevented this whole situation with a simple apology afterwards. Instead his stubbornness and pride (how proud can you be when you’re hosting a Tuesday open mic at a place called Zesty’s?) allowed this to become a human rights issue.

This has become an important issue for comedians in Canada. None of us want to sit around making safe jokes about the suburbs (Whitby) and making fun of shitty universities (Lakehead). Ethically, we are obliged to push societal taboos and challenge our audience. It is literally in our job description. So go ahead and keep doing it.

Just don’t get yourself sued. And if you do get sued, it’s probably because you’re a gay retarded Muslim woman rapist. (Thank you Charter of Rights and Freedoms.)

Special thanks to Alex Colangelo, Claire Farmer, and Katie Beahan.

Rob Norman is an actor, improviser, director, and a writer for Sexy Nerd Girl. He’s also a Second City alumnus and four-time Canadian Comedy Award nominee. You can catch Rob performing at Comedy Bar with the testosterone-infused improv juggernaut Mantown.

Auditioning requires the patience of Job, the confidence of Tony Robbins, and the love of being rejected, time after time.

As someone who’s cast hundreds of actors for commercials, here’s are some tips that can help you go from in the room to on air.

Image © Banksy

You Got An Audition! Now What?

If this is your first time auditioning, the first round is what’s known as the “cattle call.” It’s where you and approximately 300 others cram in a waiting room for one, two, sometimes three hours just waiting for your chance at 30 seconds of fame.

Read the script and memorize your lines, if any. If you have an agent, they should send you the sides (script) before you arrive. If you don’t have an agent yet, ask for the sides when you get to the casting house.

Don’t be afraid to take them with you into the audition. Sometimes they’ll have the lines written out on a whiteboard, sometimes not. Just know that we’d rather see you scanning pages than trying to remember your lines and having to be fed them during a take.

And if you’re unsure about anything, ask. Preferably before you’re in front of the camera.

Headshots

Headshots are a great investment, especially if you audition a lot. They show you’re serious about acting as a career. In Canada, you don’t need a headshot for commercials. The casting house will take a Polaroid, and staple it to your stats. You’ll need one for TV series, film and theatre auditions, though.

Make sure you keep it up to date. I’ve seen headshots that are 10 years old or more. If you’ve changed your hairstyle or colour drastically, or the photos are more than five years old, bite the bullet and get new ones.

What Allen Iverson Said

Yep, practice.

Even improvisers who are comfortable doing crazy shit on stage sometimes freeze up in auditions. That’s normal, especially your first few times. Maybe your first few dozen times.

If it helps make you less nervous, know that you’re probably not going to nail it the first time.

That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try; it just means go easy on yourself. If you leave an audition feeling like you fucked up, remember: you showed up, and you did it. That’s your success. Be proud of that.

Use your time the night before to practice your lines and play with the character. Improvise in front of a mirror, or with a friend.

As with anything, the more you do it, the easier it becomes. So take every audition you can get, because you never know when you’ll get lucky.

Be Yourself…

Whatever the role, I want to see what YOU bring to it.

Whether you’re auditioning for a principal role or a minor SOC (Silent On Camera), let your personality and point of view shine. That doesn’t mean chew the scenery; it just means relax and show us why you’re perfect for the role.

If you’re feeling nervous before the audition, practise some of Amy Cuddy’s “power poses.” They can help calm and boost your confidence in as little as two minutes.

Lastly, I don’t care if the script calls for someone in his 40s, and you just turned 21. If you own the role, a good creative will fight to cast you for it. One time a client insisted they needed an actor in his 50s for a certain role. I snuck Alastair Forbes into the audition, and he blew everyone away. The client loved him, and he booked the job. He was maybe 25.

…But Keep Improving

I always, always request actors with improv skills. But improvisers who can act? That’s the gold, right there.

If you’re an improviser, take some acting lessons. If you’re an actor, learn to improvise. Both are invaluable, and can make the difference between getting the job or not.

Dress For Success

When you get the call, find out if you need a specific wardrobe. I know actors don’t have unlimited budgets, so if you don’t have it, borrow from a friend, or visit your local Value Village.

Otherwise, err on the side of business casual. A solid shirt and pants or nice jeans for guys, and a dress that doesn’t show too much skin for the ladies.

Some actors wear the same thing to callbacks that they wore to the initial casting. I’ve heard some actors do it “for luck,” because they think that somehow that paisley shirt and ripped cargo pants got them the callback.

In a word, no.

I can look past superfluous stuff, but many advertising people can’t. And even if my art director and I love you, if we can’t sell you to our boss or clients because they’re fixated on your Metallica t-shirt, it’s game over.

Give yourself the best possible odds. Dress the part.

A Note On Grooming

Beards are popular these days. But unless the role calls for a hipster, 99% of clients see “prisoner” or “pedophile” when presented with facial hair.

Shaving your beard, or at least trimming it down to Henry Cavill proportions, will increase your casting potential a hundredfold.

And never, ever cut your hair right before a shoot.

I once cast an actor with shoulder-length hair. She showed up on set two days later with a pixie cut. It’s the kind of thing that makes clients go ballistic – and can get you fired or blacklisted.

Even if you’re just contemplating a trim, always ask before doing it.

Be Professional When Those Around You Are Not

When you walk into a callback, there’s usually a producer, writer and art director sitting at the director’s table.

Sadly, many advertising creatives are oblivious to the actors in front of them. While you’re trying to rock your best Guy #2, they may be whispering, eating, scribbling, absorbed in their iPhone, or thinking about their next meeting with a face like thunder.

Ignore them.

Greet everyone with a smile as you walk in the room, then give your full attention to the director and/or camera.

Even if some people are focused elsewhere, a good director will take note of your performance and review it after the casting.

Agents And Stuff

You don’t need an agent to land gigs, but it helps. The catch? Most agents prefer that you already have a few roles under your belt before they’ll take you on.

Cameron and I have auditioned friends who didn’t have representation, and a number of them caught the eye of casting directors, who helped them find an agent. Look on Facebook or network with your fellow actors to find out about upcoming auditions.

However you get in the room, it’s important to know that once you’re there, if you’re good, you will get noticed.

You Got The Part. Now What?

Congratulations! You beat out dozens of other hopefuls, and now you’re ready for your close-up.

If this is your first on-camera role, you’re probably a little anxious. Try some simple breathing exercises to calm you. (You can listen to them on headphones on the way to the shoot.)

Allow yourself plenty of time to get to the location. Use Google maps the day before to gauge how long it will take you.

Once you’re on set, there’s a whole crew of highly-trained people, from hair & make-up, wardrobe, and script continuity, to the producer, AD, and director, whose job it is to help you give the best performance.

Take a deep breath, and enjoy the ride.

You Didn’t Get The Part. Now What?

Know that you’ll fail far more than you’ll succeed in getting roles. That’s not just you, that’s the business.

Even if you own the role, out-Brando Brando, or make everyone in the room laugh, you still might not get the part. I’ve seen actors rejected for being too tall, too round, too thin, too short, too good looking (yes!), not good looking enough…and the list goes on.

As personal as some of it sounds, don’t take it personally.

You have something to offer that no one else ever has, or ever will. Don’t let a handful of people determine how you feel about yourself.

It’s Not An Audition, It’s A Performance

If you treat every audition not as a dress rehearsal, but as the real deal, you’ll always bring your best self. And there’s no better gift you can give the world.

Speaking of gifts, watch Bryan Cranston’s advice for aspiring actors. It’s priceless.

Now go out there and knock ’em dead. I’ll be cheering for ya.

For more tips, check out 21 Things That Make Casting Directors Happy. It’s not just great advice for auditioning; it applies to every part of your life.