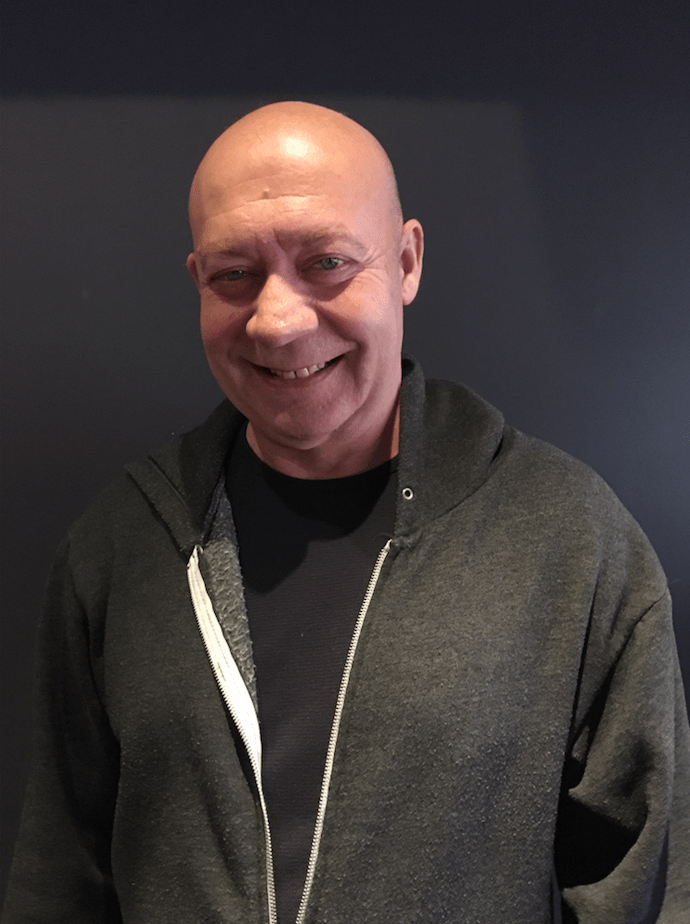

Rob Norman is an actor, improviser, director, and a writer for Sexy Nerd Girl. He’s also a Second City alumnus and four-time Canadian Comedy Award nominee. You can catch Rob performing at Comedy Bar with the testosterone-infused improv juggernaut Mantown.

I don’t know you (or maybe I do; it’s hard to see your face past this dense, ethereal veil known as “the internet”) but I’m going to guess what your problem is: You don’t have any money.

That’s obvious. You’re reading a blog about improvisational comedy. Only a working comedian trying to unlock the secrets of their craft would think that’s a good use of their time. Or you’re a very, very bored poor person. Either way, you should probably be on Craigslist finding a real job. Shame on you.

Onstage, your improv-related problems are idiosyncratically linked to whatever psychic inadequacies you possess. Each show is a battle fought with internal reminders: Stop trying to control everything. Build on other people’s ideas. Be more vulnerable. Stop trying to be entertaining. Create scenes that make sense.

Despite knowing what you should do, it seems you can’t help but repeat old habits. So for the next fifty kilobytes, let’s abandon the idea of doing “good improv.” Instead let’s focus on improvising more efficiently. After all, you have limited resources (stage time, energy, the audience’s goodwill).

Great improvisers seem to float through scenes without ever wasting a single line of dialogue, while struggling newbies flail about aimlessly, creating superfluous information that only serves to confuse everyone onstage. So how do you focus on the essentials in a scene?

Player A: Oh no, Jim! My best friend of fifteen years. Look, this nuclear bomb is about to explode.

Player B: Quick. Let’s try to fix it!

Player A: Yes and…we did it.

Player B: Hooray!

Great “Yes anding.” Unfortunately, I couldn’t care less. Why do we put so much focus on imaginary things? I don’t care about the nuclear bomb. And your special effects are unimpressive (the drunken audience’s imagination plus your mime skills do not a good scene make).

I also don’t care about the story. If the bomb blows up, it’ll irradiate an imaginary mall and kill two made-up characters (that no one cares about) with a fictitious backstory that probably wasn’t compelling to begin with.

But there is something real happening onstage: the dynamic between you and your scene partner.

Behaviour is what draws us into your scene. It’s the only thing we see onstage and recognize as true.

You’ll be a better improviser when you stop seeing what could be (or should be – all those helpful improv rules you’ve learned) happening onstage, and start reacting to what’s happening right now, in front of you.

Player A: Here’s my test, Dad. I think I failed.

Player B: That’s terrible. You’re grounded until your marks improve!

Does this sound like a decent improv scene to you? Do it onstage, and watch what happens. At worst, it bombs. At best, it bombs with some funny moments. But why is that? Both players are adding information in a simple fashion. They’re developing the scene together.

The problem is, the star of this scene isn’t Player A or Player B. It’s about some imaginary kid (don’t care) and his grades in school (I also don’t care). For the most part, real kids in real schools living real lives don’t care about their grades. Why would you want to make that the focus of your scene?

An improviser’s only job is to create a dynamic between the characters onstage. It’s how you’re affected by your scene partner that pulls us in. Each time your partner adds information, ask yourself, “Do I love or hate what was just said?”

Player A: Here’s my test, Dad. I think I failed.

Player B: Go fuck yourself!

Whoops! You’re not choosing whether you love or hate your scene partner in their entirety. This is equally boring. It creates a dynamic that exists entirely in the past. You’ve already made a firm decision about your scene partner and there’s no room to build (or heighten the pattern). Instead, think “Do I love or hate what my partner just said?”

Player A: Here’s my test, Dad. I think I failed.

Player B: Oh that’s the worst! Now you’re not going to amount to anything!

Player A: It’s only a test…

Player B: I can’t believe you think that. You’re a failure and naïve!

Great! So each time Player A speaks, Player B is affected personally by it. And Player B has chosen to hate it. But the reverse also works.

Player A: Here’s my test, Dad. I think I failed.

Player B: You are so brave for telling me!

Player A: Dad…

Player B: It takes one hell of a man to look his father in the eyes and admit he failed. I’m going to buy you a car.

Player A: I’m fourteen.

Player B: But with the integrity of a man in his eighties!

Also great! Do you see how both of these examples are happening right now? It’s not about the failed test, it’s about how a kid tells his Dad he failed the test. Do you see how both players are forced to immediately respond? Everything else: characters, environment, action, story – are just by-products of being in the moment. And the context of your scene is an imaginary (and often accidental) construct generated by actively playing the dynamic.

And that’s something you can easily create. Try it. Let your scene partner speak, then decide to love or hate that idea. Once you’ve mastered that, expand “love” to any positive emotion (contentment, admiration, lust, comfort) and apply that to your partner. See what happens when you use the same technique with negative emotions.

In the end, there are two kinds of improvisers: Players who invent information. And players who discover information.

You can make a scene happen, or let your scene happen to you. If you focus on creating less, you won’t have to improvise in the future or the past. You can spend more time with your scene partner. Onstage. In the moment. Inside of the scene. And less time reading improv blogs on the internet. Seriously, you really need to find that job…

Photo © Kevin Thom